Context

For our work on the brake triangle, I was part of a team of four engineers tasked with

reproducing new brake triangles compatible with the CC2200 and CC3300AC locomotives. We were

required to manufacture two different brake triangles to address the problem of stock

shortages, as these locomotives were very old and their spare parts were no longer available

on the market. It was therefore necessary to produce their components locally.

The objective was to design a system that closely matched and remained fully compatible with

these locomotives while ensuring acceptable durability and functional performance comparable

to the original imported parts.

As part of the project requirements, we transitioned from the older Shielded Metal Arc

Welding (SMAW) method—commonly known as arc welding with coated electrodes—to more advanced

welding techniques: MIG-MAG (Metal Inert Gas – Metal Active Gas). This shift aimed to

improve weld quality, structural integrity, and compliance with the structural standards and

regulations of the Cameroonian railway system.

To facilitate this change, we were equipped with the Lincoln Electric Power MIG 360MP and 2

Fronius TransSteel 2700.

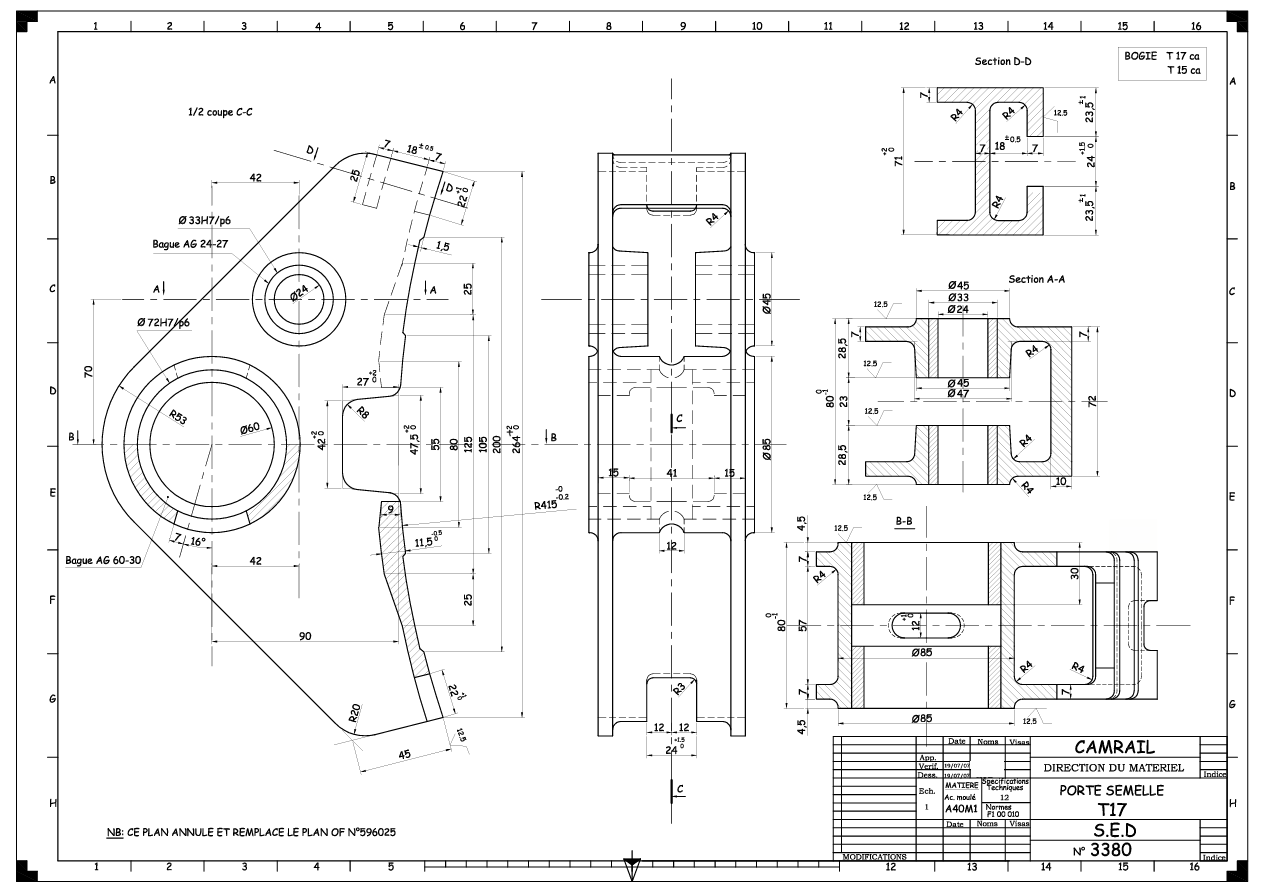

My specific objective in this project was to produce detailed 2D diagrams and 3D models,

ensuring that all dimensions and tolerances remained within acceptable limits. This was

essential to guarantee that the brake triangles could be easily integrated into the

locomotives and perform the same function as the reference components.

Content

In this project, our team of four (consisting of Gille team lead, Mbella Jacques chief

technician and his assistant Ricardo) produced two brake triangles: one for the CC2200

locomotives and one for the CC3300-AC locomotives. Each brake triangle had distinct

specifications, including different diameters and dimensions, which required careful

planning

and collaboration within the team.

For the CC3300, we utilized UPN profiles, which we bent and cut into the required shapes. Our

team added end caps to achieve the correct mass while maintaining the necessary diameter.

Following this, we reproduced the front shoes. I was responsible for creating detailed 2D

drawings and 3D models of the front shoes. Using calipers, measuring tapes, and other

traditional reverse engineering methods, I ensured that these components were not only

accurately reproducible but also fully manufacturable, in alignment with our project

objectives.

For the CC3300-AC, we machined rectangular iron bars and shaped them into circular forms,

closely matching the existing brake triangles. By applying traditional reverse engineering

techniques—including manual measurement, geometric analysis, precise dimensioning, and

tolerance verification—I produced precise and manufacturable 2D drawings. This approach

ensured that each assembly fit accurately and that the components could fully reproduce

their

intended function.

During the project, I worked closely with my team. I helped in the organization of tasks. I

also shared ideas and suggestions to help the project move forward (the ideas for the end

caps were mine). By working together, we completed all the steps—from machining the raw

material, welding the different components, to testing them—to ensure they matched the

function and characteristics of the original brake triangles.

Conclusion

Through this project, I learned an important lesson about the value of collaboration between

designers and manufacturers. In my experience, when working in a design office, it is easy

to

assume that theoretical work—such as 3D modeling and detailed drawings—is sufficient to

produce a component. We sometimes think we can complete a design without consulting the

manufacturer.

However, this project demonstrated how critical the role of the manufacturer is. They not

only

help you understand appropriate tolerances based on the materials and machinery available

but

also enable you to complete the work more efficiently. For example, during the reproduction

of the front shoes for the CC3300-AC locomotives, I initially applied tolerances that were

not suitable for manufacturing because I assumed that their tools and capabilities were the

same as those I had encountered in previous workplaces.

This approach cost the team a significant amount of time, as we constantly had to review

details and ensure that the dimensions were both acceptable and manufacturable. From this

experience, I gained a deeper understanding of practical dimensioning techniques and learned

how to work humbly and effectively with the manufacturer. By consulting them during the

design process, we were able to reduce errors and save time.

"If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together." In

my case, especially, working alone often led to mistakes, whereas collaborating closely with

the team and manufacturers resulted in fewer errors and faster, more accurate outcomes.