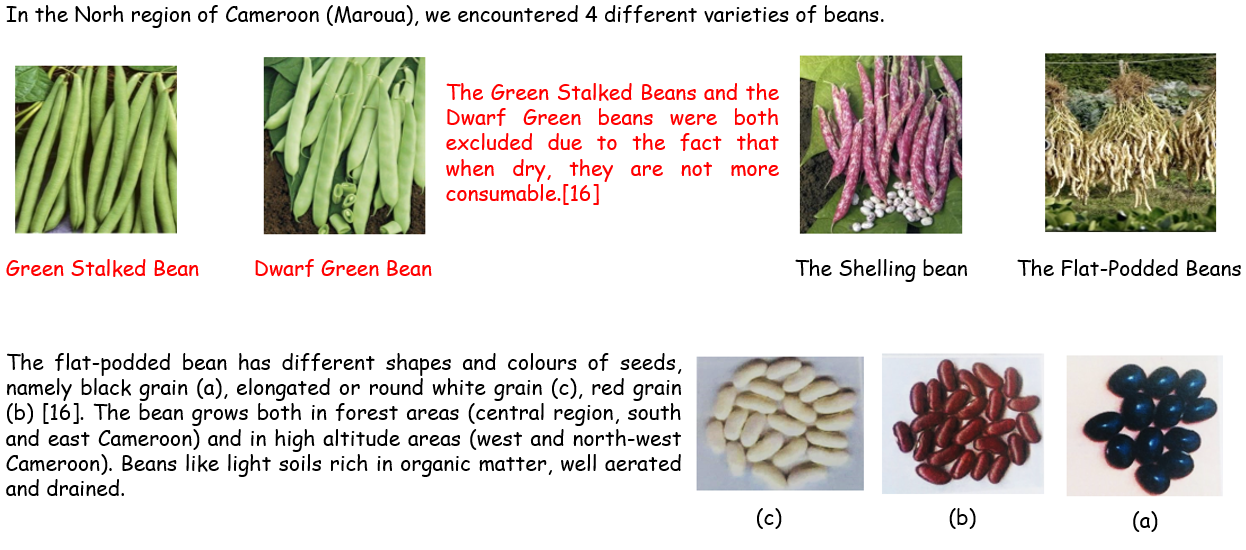

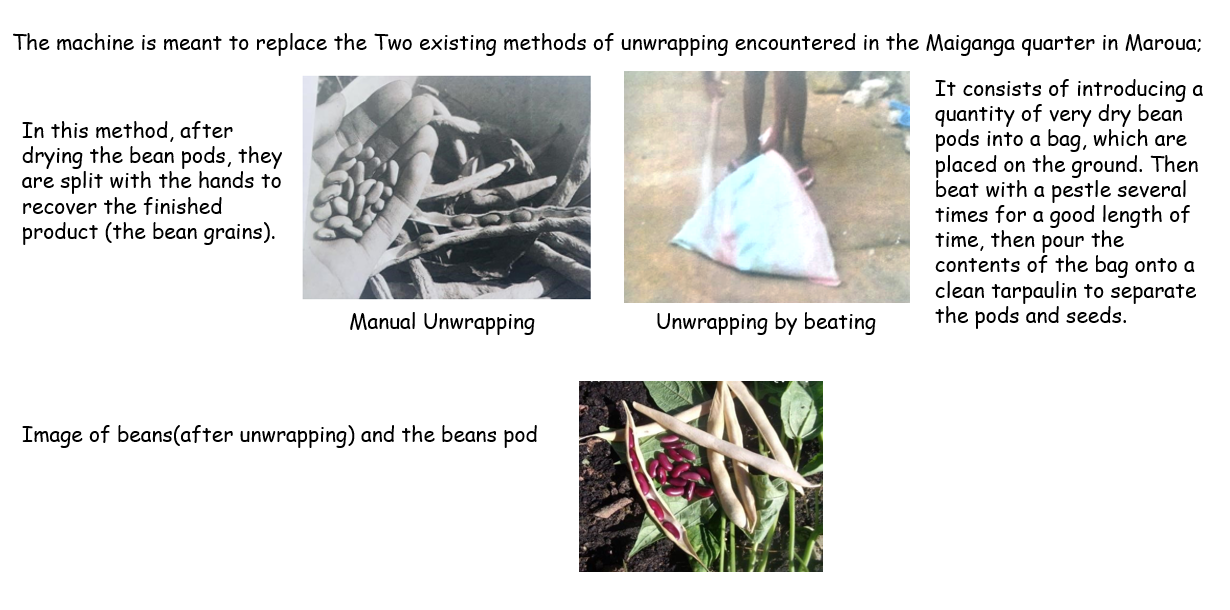

Context

During a visit to Maroua in northern Cameroon, I observed local farmers manually unwrapping

beans—a process so slow and labor-intensive that it severely limited production efficiency.

This firsthand encounter with traditional agricultural methods sparked my decision to design

an automated solution addressing the needs of small and medium enterprises across Central

Africa.

Working independently over two months, I sought to develop my machine design competency while

creating a practical tool for communities facing these challenges. The project required

balancing technical performance goals—achieving over 85% yield, reducing operator physical

effort, and ensuring health and safety standards—with the reality of limited material

availability and the need for straightforward maintenance in rural settings.

Content

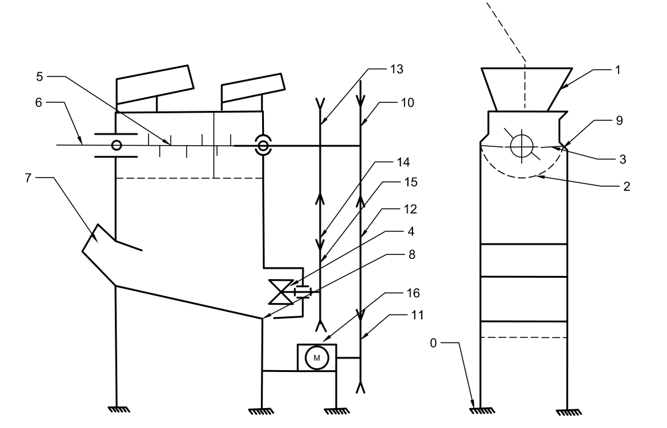

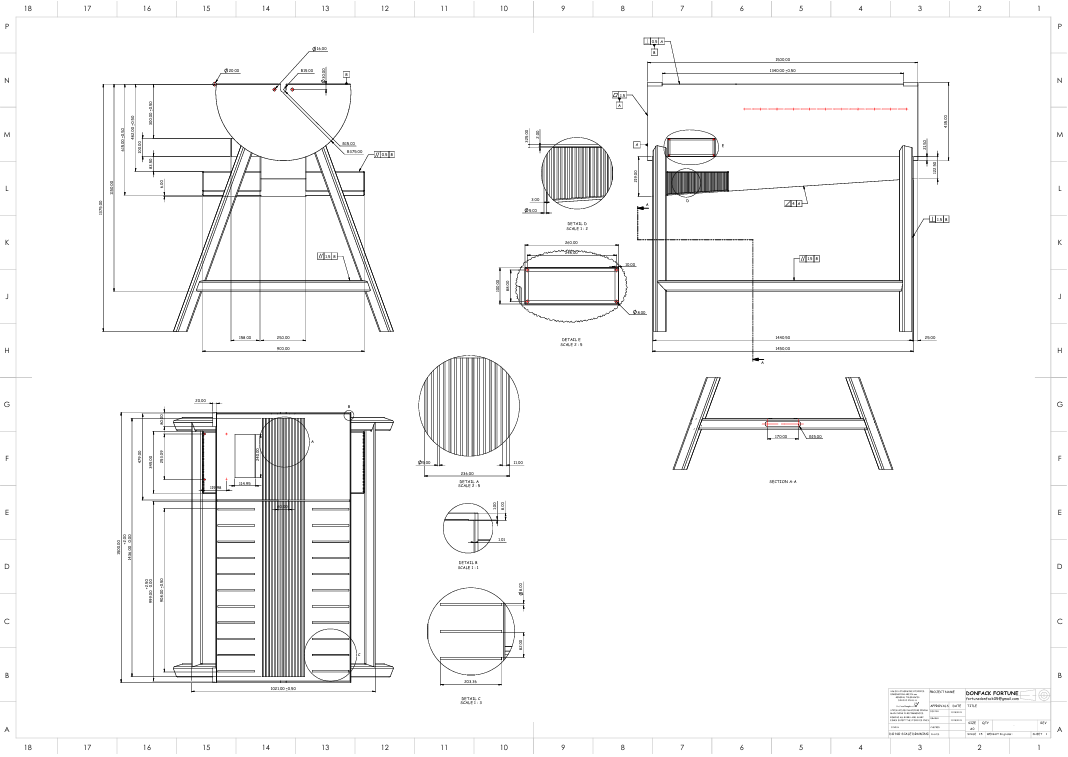

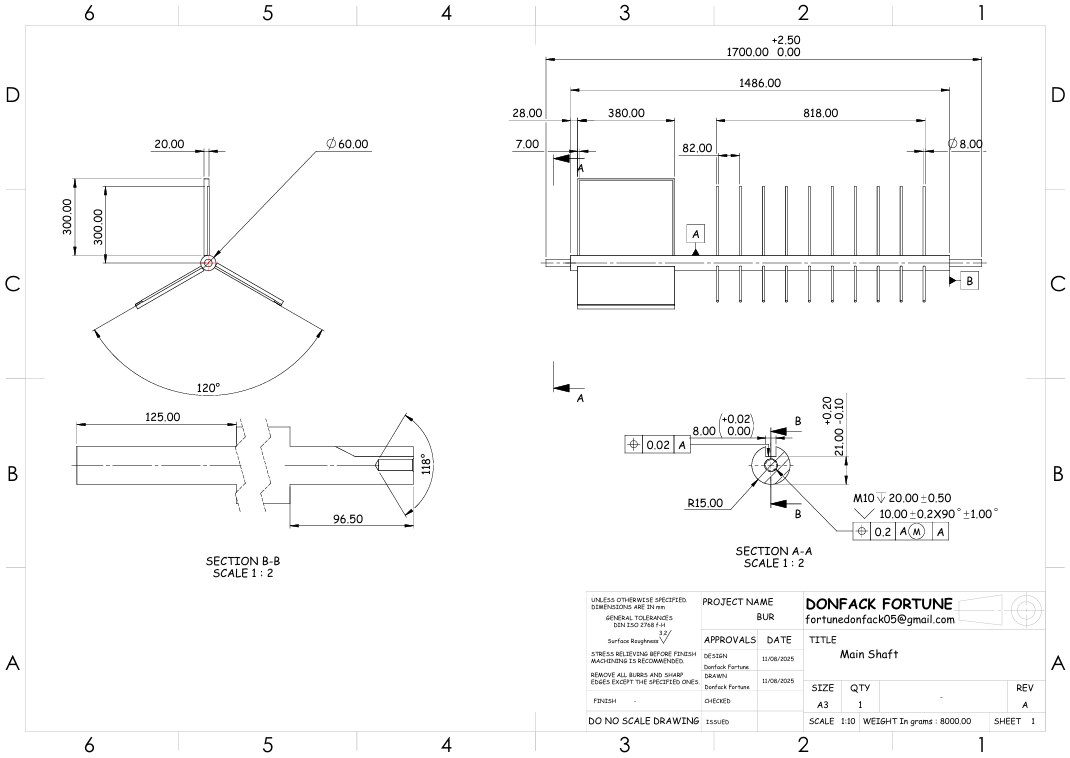

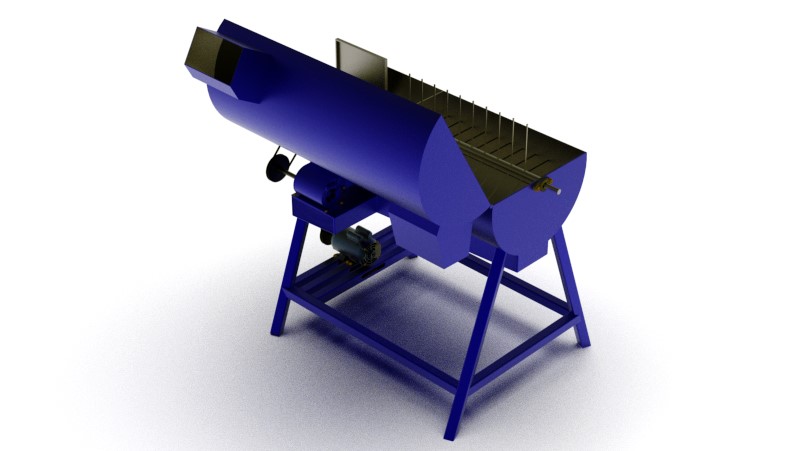

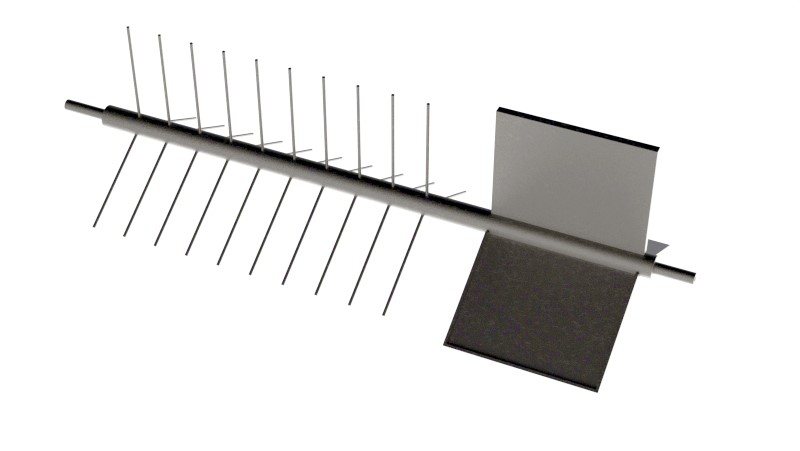

I led the entire research, ideation, and design process, developing competing prototypes

before selecting the final configuration based on raw material availability, parallel motor

positioning, and fan placement for optimal stability and reduced vibration. The shaft design

became critical—I engineered variable-dimension blades mounted at 120-degree intervals with

5cm spacing to ensure proper bean unwrapping without breaking, carefully calibrating

rotation speed against the motor's driving force.

Power transmission employed a double-groove pulley system connecting motor, shaft, and fan to

partition driving force efficiently. When the specified 1.1kW motor proved unavailable, I

adapted the design for an alternative motor while maintaining performance targets. I

prioritized compact assembly through flexible CAD modeling, positioning the pulley and belt

externally for easy interchangeability and providing direct shaft access for refinement and

repair. Steel thickness selection balanced structural integrity against overall machine

weight, a decision crucial for the portability farmers required.

Conclusion

This project fundamentally shaped my understanding of design for constrained environments.

Working with Nepitimbaye, Grace, and Tatsinda taught me that technical excellence must

accommodate real-world unpredictability—their perspectives on material substitution and

component failure modes proved invaluable when ideal specifications couldn't be met.

I learned a crucial lesson in team dynamics: as the project evolved from solo design to

collaborative implementation, I discovered that the effort invested in communication and

skill-building pays compounding dividends. Initially, I defaulted to executing small tasks

myself rather than spending time explaining requirements. However, once I committed to

thorough onboarding, the team operated increasingly autonomously, extrapolating from base

principles to solve problems independently. This experience reinforced that "doing it

yourself" is rarely optimal—setting teammates up for success through clear communication and

patient teaching yields far better outcomes than shouldering every responsibility alone.